Indian healthcare is a mirror, revealing who we are as a country: our inequalities, hopes, and contradictions. If you ask one simple question, Who is an Indian doctor?, you will quickly find it’s a more complicated question to answer. Behind every prescription pad is a different story, a different path, a different doctor; some walk hospital hallways through shiny and high-tech metros, some brave caked and dusty village roads. All have the same responsibility: healing in a nation where medicine is much a lifeline than a profession.

I was asked to write about “a day in the life of an Indian doctor”. I thought it was harmless enough. Until I hit pause and asked myself: Which Indian doctor? The cardiologist at a private luxury hospital in Gurgaon, who trained in London and drives home in a BMW? The government MBBS doctor treating 120 patients a day in a third-tier town? Or the unlicensed but integral village “doctor” whose name is not in any medical database but whose phone rings at 3 am every night and every time of day? There is not a single portrait. Only a mosaic.

The General Practitioner: Disappearing Bedrock of Trust

Once the rock for Indian healthcare, the local general practitioner who knew you and your family by name and could cite your grandmother’s sugar levels even better than you could, the general practitioner, is becoming a thing of the past. Mostly MBBS trained, sometimes not, these doctors treated patients like people, not just numbers. They arrived at your home at 2 a.m. when your kid was crying or when your elderly neighbor had collapsed. They used to charge what patients could afford, not necessarily what the market should have suggested. For several generations, they were a family’s first and sometimes only hope.

The AYUSH Doctors who Exist in Between

AYUSH doctors are doctors trained in Ayurveda, Unani, Siddha, and Homeopathy, are filling the holes where allopathy leaves off in many small towns and rural areas. Not because they believe in the ideology, but because they need to. Their clinics are basic. A steel, rusted almirah. A plastic chair. Maybe a stethoscope. But their prescriptions look like what doctors prescribe; that’s what patients want. In practice, they often give antibiotics, pain killers, and drips. “I am an ayurvedic doctor,” said a physician from Bundelkhand, “but nobody wants slow treatment. They want results. If I don’t give it to them, they will go to someone who will.” They say it’s not malpractice. It is how they survive. And their patients as well.

The Informal Healers- Overlooked and Essential

You will find them in the margins. They go by many names: jholachhaap, rural RMP, quack. With no degree but no shortage of patients. In places where the nearest hospital is 50 kilometers away, inhabiting the margins is the only option. Their formal knowledge is a mix of apprenticeship, instinct, and trial and error. The medical establishment condemns them. But from the perspective of villagers, they are applauded. “I know he’s not a real doctor,” says a native person. “But when my son was having a fever, he came on a bicycle at night. Show me one government doctor who would do that.”

In some districts, informal practitioners provide over 70% of all primary healthcare. They operate in the grey. But in India, grey is frequently the place where reality lives.

The Specialist- Operating the Parallel System

Then there’s the specialist, the MD, MS, or DNB-sanctioned specialist. They are running nursing homes, performing surgery, and managing ICUs. They are respected and relied upon as they also work themselves to the bone. But they are also going to have to be administrators and entrepreneurs, problem-solvers. A doctor in India with a private clinic doesn’t just see patients. They negotiate with electric companies, oversee HR, repair leaking plumbing, and keep the books. “It’s harder than my residency,” says Doctor, a gynecologist. “I can deliver a baby easily, but running a hospital without going bankrupt is hard.”

And let’s recognize their institutions, often just modest buildings and even businesses hidden away in backstreets that have saved millions. Hospitals are often never celebrated or regarded as resources, born out of necessity and through sheer personal persistence.

The Superspecialist-Technology’s Flagbearer

In urban centers of India, a different kind of healthcare provider emerges as the superspecialist. Trained in one hyper-specific area of medicine, cardiac electrophysiology, pediatric neurosurgery, and reproductive endocrinology, they operate from a pedestal, working with state-of-the-art robotic arms and imported implants. This is the vision of the future of medicine. But also, the vision of inaccessibility.

“Most of my patients are coming through insurance or high-end referrals,” says an esteemed neurosurgeon. “We have made incredible progress. But at times, I wonder: are we doing great things for India, or simply replicating the West?” In a country where 63 million people fall back under the poverty line because of out-of-pocket healthcare expenditure each year, this is not a rhetorical question.

The Medical Educators: The Keepers of the Flame

Behind every doctor is a teacher. They don’t wear Rolex watches, they don’t create Instagram reels, they don’t become YouTube stars. But they do shape generations. Medical faculty in particular, in government colleges, contend with daily strife: negligence of infrastructure, obsolescence of syllabi, inadequate pay, and yet they show up.

They oversee cadaver dissections in the morning, and then by noon are embroiled in a debate over ethical dilemmas. They author textbooks and review manuscripts. Credit is seldom claimed. Their classrooms are the unseen battleground of India’s health care system, the arena where its future is not just taught, but constructed.

The Activist Doctors-Healing a Nation, Not Just a Body

And then we have the outliers. The idealists. The doctors who abandoned comfort for crisis. They didn’t just treat a vector-borne illness like malaria or a hemoglobinopathy like anemia. But they treated malnutrition, illiteracy, and state apathy.

They wielded simple tools. A stethoscope, a bicycle, and a sense of justice. They looked upon healthcare, not merely as a service that existed, but as resistance; a means of reclaiming dignity for the unrecognized.

Conclusion:

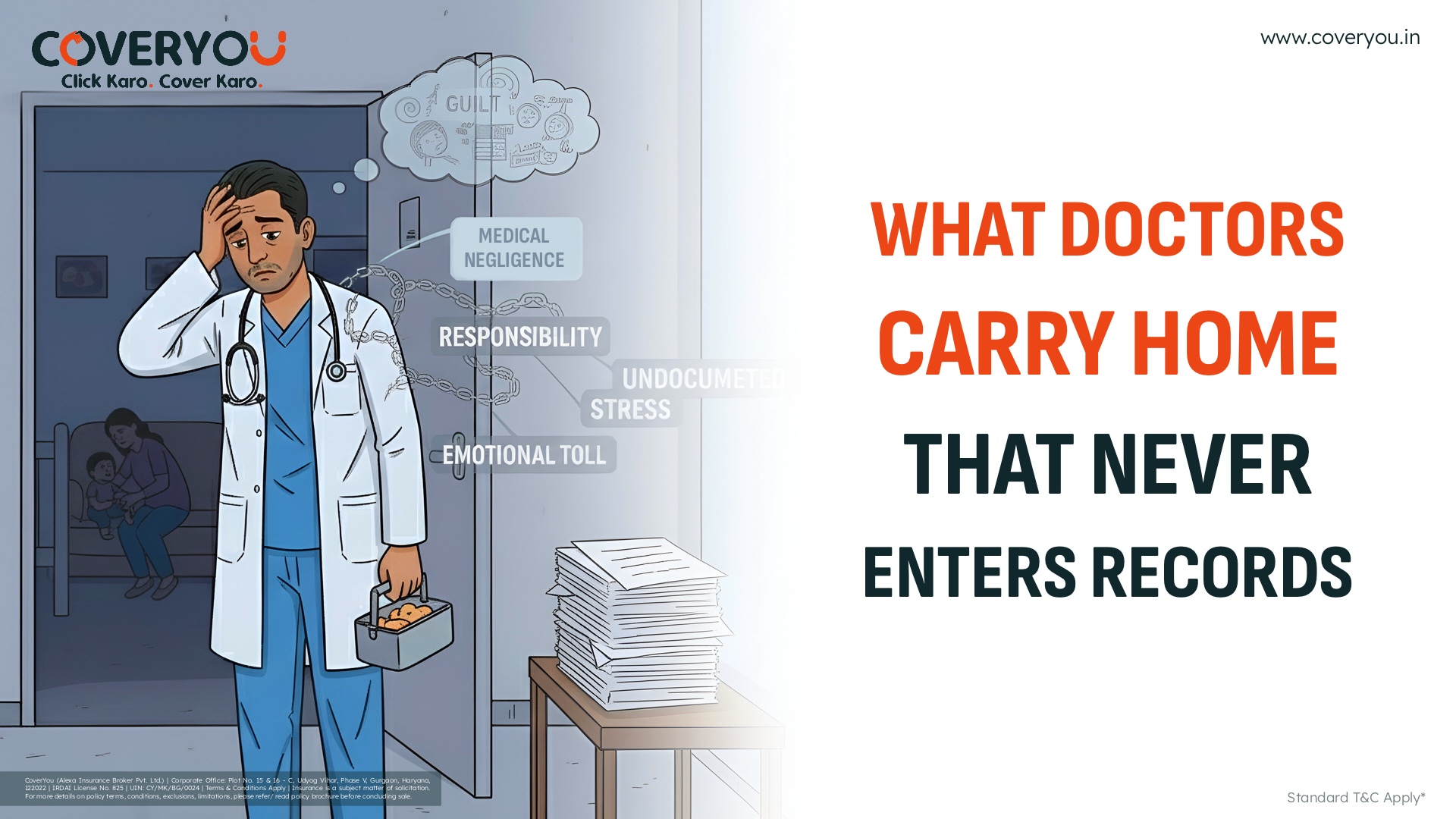

There isn’t an easy answer to the question, “Who’s the Indian doctor? ” The fact of the matter is the Indian doctor isn’t a single person; they’re a collective heartbeat. They exist in all environments, some in shiny, busy ICUs, others riding creaked-out bicycles along flood zones, and many giving lectures, encouraging the next wave of doctors to remain curious. Some are rewarded, some remain in the background, and some aren’t even known as doctors in the first place.

But every day and every night, they toil laboriously to sew this nation back together, diagnosis by diagnosis. To reduce their experiences to one story would be inaccurate. To pay homage to only one would be unjust. The truth is, Indian healthcare is not necessarily about the infrastructure or the policies; it runs on the individuals working behind it. It’s the tired faces, the middle-of-the-night phone calls, and the hard choices made with few resources but endless will. This is not just a day at work; it’s a lifetime of commitment by way of millions.